(0302) Woke up early. (0357)

5. Isn’t physics fun?

4. Who’s the real President?

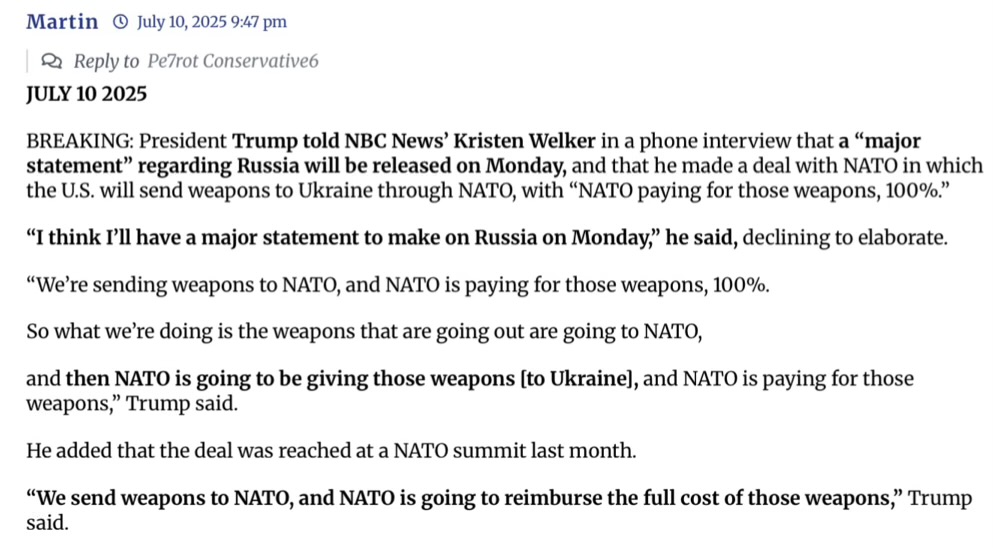

3. Here’s a fun read

… ta, Redacted:

2. Will they nail Singham or will they not?

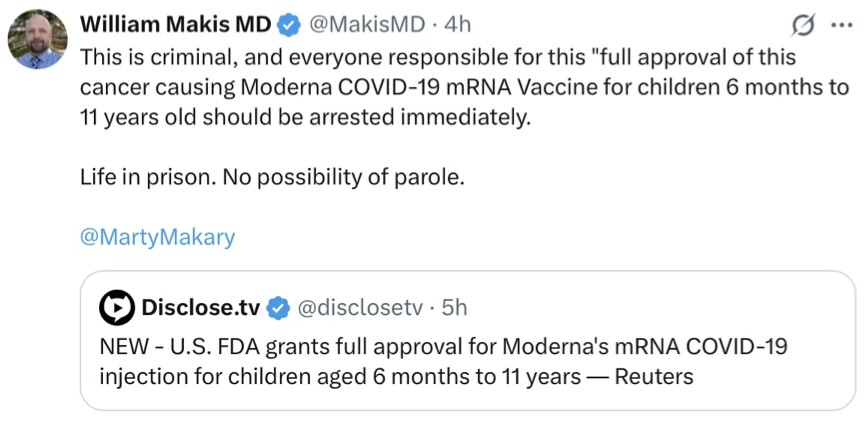

Meanwhile, more fun for the children and elderly … so well protected today don’t you think?

1. Y’all have a nice weekend, y’hear

Have a nice Saturday and a nice Sunday too, stay well.

1 nice w/end

interesting vids.

long term h’wood attorney, with much “scoop” on the place.

kinda surprised he hasn’t been unalived yet.

https://www.kimdutoit.com/2025/07/10/bare-ruind-choirs/

Bare Ruin’d Choirs

JULY 10, 2025 KIM DU TOIT DEEP THOUGHTS

When King Henry VIII ordered the destruction of Catholic monasteries and cathedrals, what was left were skeletons of buildings, and their bleakness was captured by both Shakespeare and, later, Wordsworth. The entire Catholic world was overturned, and the spiritual desolation of the worshipers must have been horrifying. They were, however, in the minority. Worse was to come.

I first read Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables in the original French, and sadly, spent so much time grappling with the translation of the 19th-century French that I never did appreciate the novel fully. In fact, I wondered what all the fuss was about: the novel, by modern standards, was hopelessly long-winded, had all sorts of irrelevant characters to the plot, and so on. Then, some dozen years later, I found a brilliant translation and read that, and all my earlier scorn for Hugo disappeared.

In that monumental work was the entire catalog of human existence: love, death, betrayal, forgiveness, venality, cruelty, compassion and kindness, to name but some. The panoply of Man’s humanity and inhumanity was all there, laid out like a feast on a table, all for the reader’s tasting; and then came Inspector Javert.

Suddenly, there was a sinister addition to Hugo’s comédie humaine: the State. The State, with all its papers, its registrations, its mindless bureaucracy, and its wheels of justice, grinding slow and grinding extremely small. Suddenly, the story of Jean Valjean, which could have been told in just about any age, now became a modern story. And suddenly, the balance between justice and mercy, once the provenance of God, had been transferred to the State – and the State, as personified by Javert, had no mercy, only justice.

The order of the world had been overturned; the old order had disappeared, and been replaced with something different, something ineffably worse.

At first, I thought that this was it: one world had ended, another had taken its place, and sure, Hugo’s work was fiction after all, and such wrenching change was uncommon, perhaps a once-in-several-millenia occurrence.

Five years later I read the Loss Of Eden trilogy by John Masters. In Eden, Masters describes in minute and appalling detail how an entire civilization disappeared as a result of the First World War. Like the appearance of the impersonal State bureaucracy in Hugo, the modern manifestation of the State was its impersonal application of technology to the wholesale slaughter of the opposing army. In Les Misérables, the bureaucrat Javert at least had the option of solving an insoluble conundrum by his own suicide. No such option existed for the generals on the Western Front. The result was the disappearance of an entire generation of young men, a decimation or worse of lower- or middle-class youth, and the virtual disappearance of the upper class, doomed by their class and upbringing to lead their men into the hot mouths of the machine guns, and to suffer disproportionately.

At a stroke, the old ruling class disappeared, whether by slaughter on the Western Front, or by revolution in Russia. In its place came the modern government bureaucracy: more faceless than before, more powerful than before. The post-Great War government was to rule not by divine dogma, nor even by royal whim, but by cold, impersonal philosophy. After the Great War, literature (and the arts in general) fell into the hopeless nihilism of Dada and the antiwar horror of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet On The Western Front. The Second World War, a continuation of the Great War’s slaughter, was brought to its apogee by the killing of thousands by a single bomb, twice. What the Second World War enabled was the growth of the Leviathan state, with its impersonal bureaucracy (like mass destruction) brought to its ultimate conclusion. Instead of the post-Great War Dadaism, post-Second World War literature was defined by bleak dystopian visions like George Orwell’s 1984 and absurdist plays like Samuel Becket’s Waiting For Godot.

Movies have progressed into huge, totalitarian productions like Avatar and Titanic, winning awards not because of their literary or cinematic brilliance, but because of their astronomical production costs. As a reaction, my taste in movies has moved towards the little, personal movies like Sideways and The Cooler. In contrast, however, my taste in literature has been influenced by the immensity of Les Misérables and Loss Of Eden, where whole societies come to an end, and the misery of human existence is captured in all its facets.

I have no idea how much the Information Revolution is going to change society. All I know is that it will. However, if I want to see how we will be affected by the next overturning of society, and get an idea of the misery we will endure, I just have to re-read Les Misérables and Loss Of Eden.

This time, Shakespeare’s “bare ruin’d choirs” will not be in our buildings, but in our souls.

I wrote this in late 2010. As far as I can tell, not much has changed since then.

R